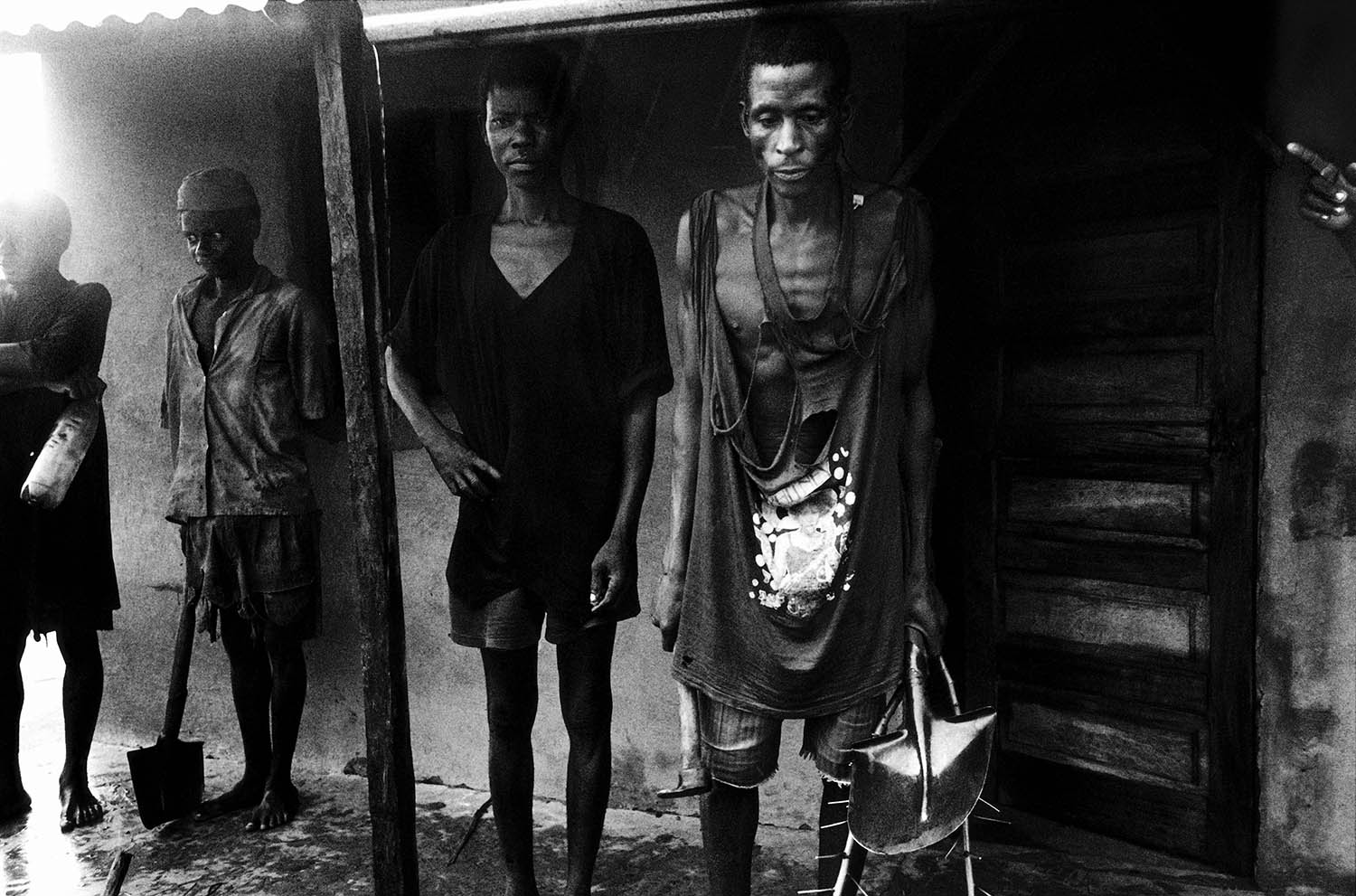

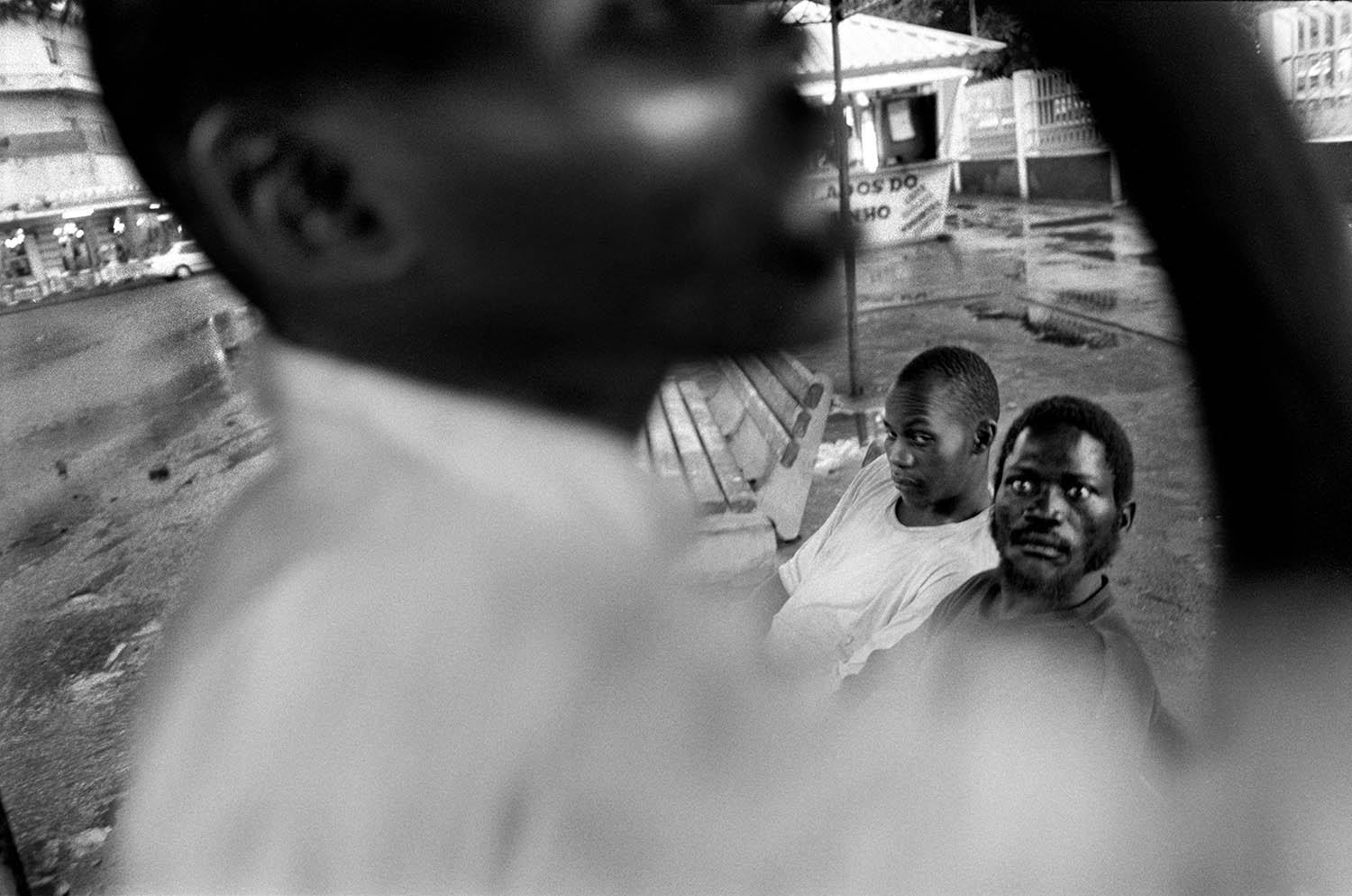

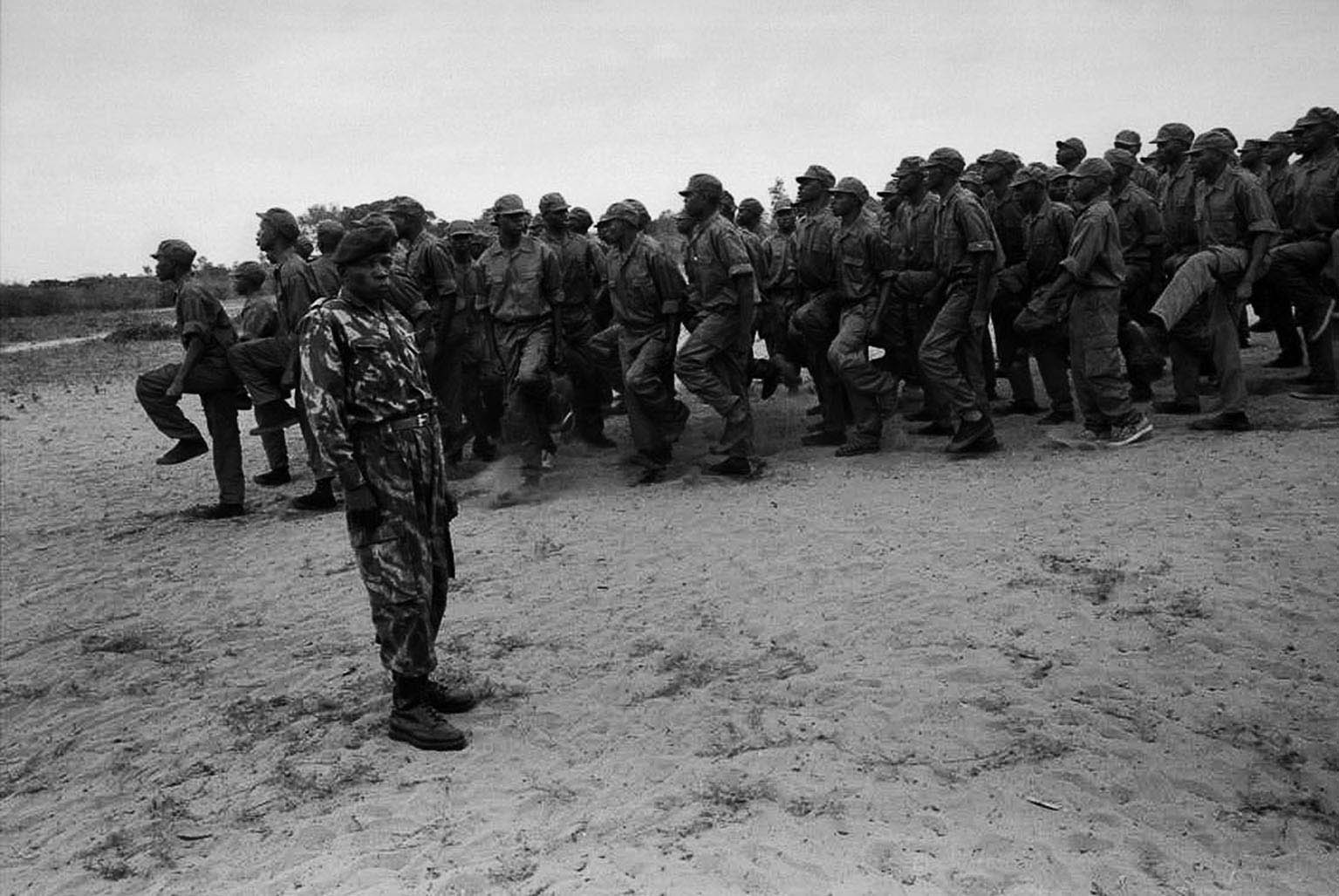

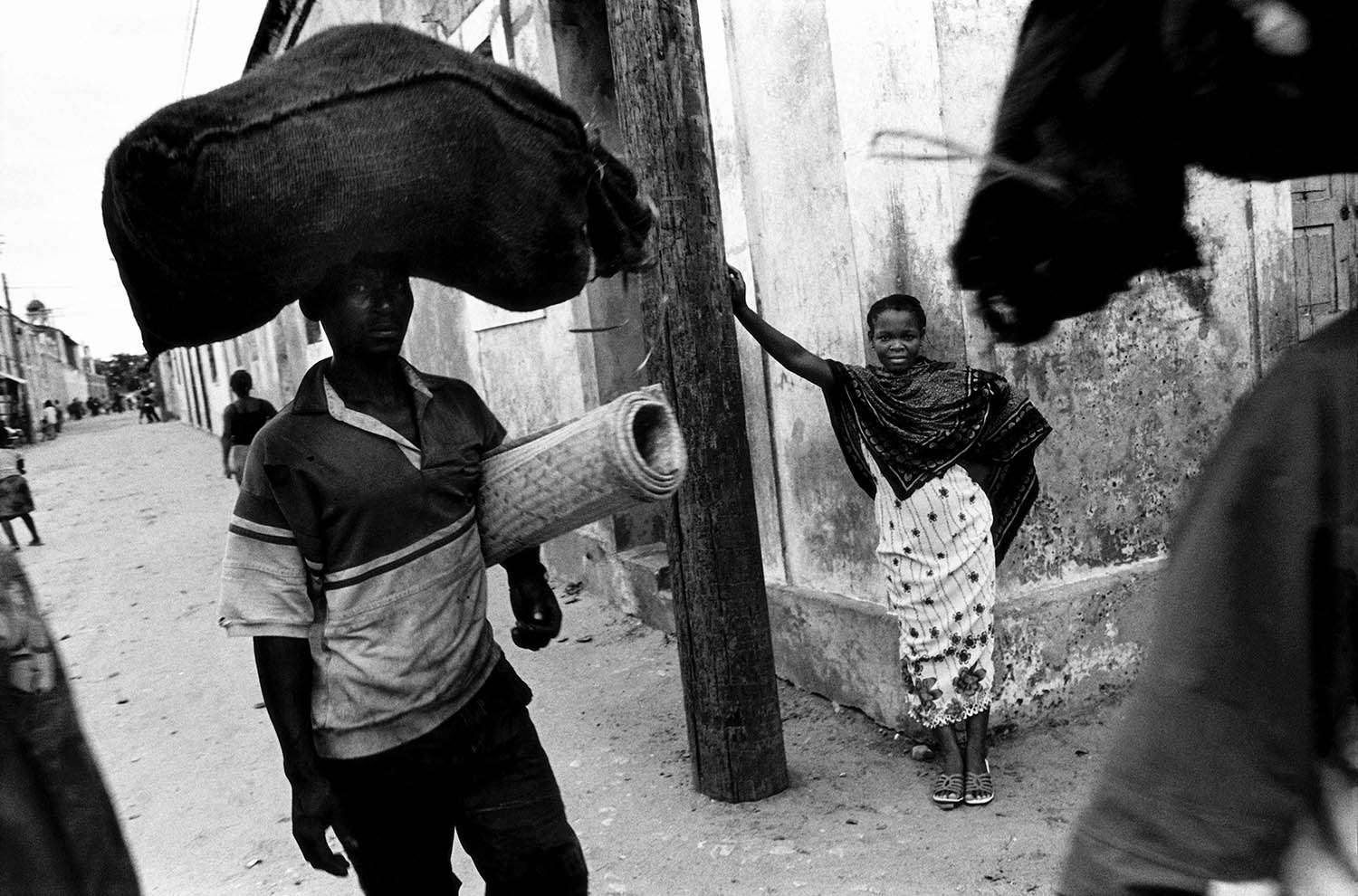

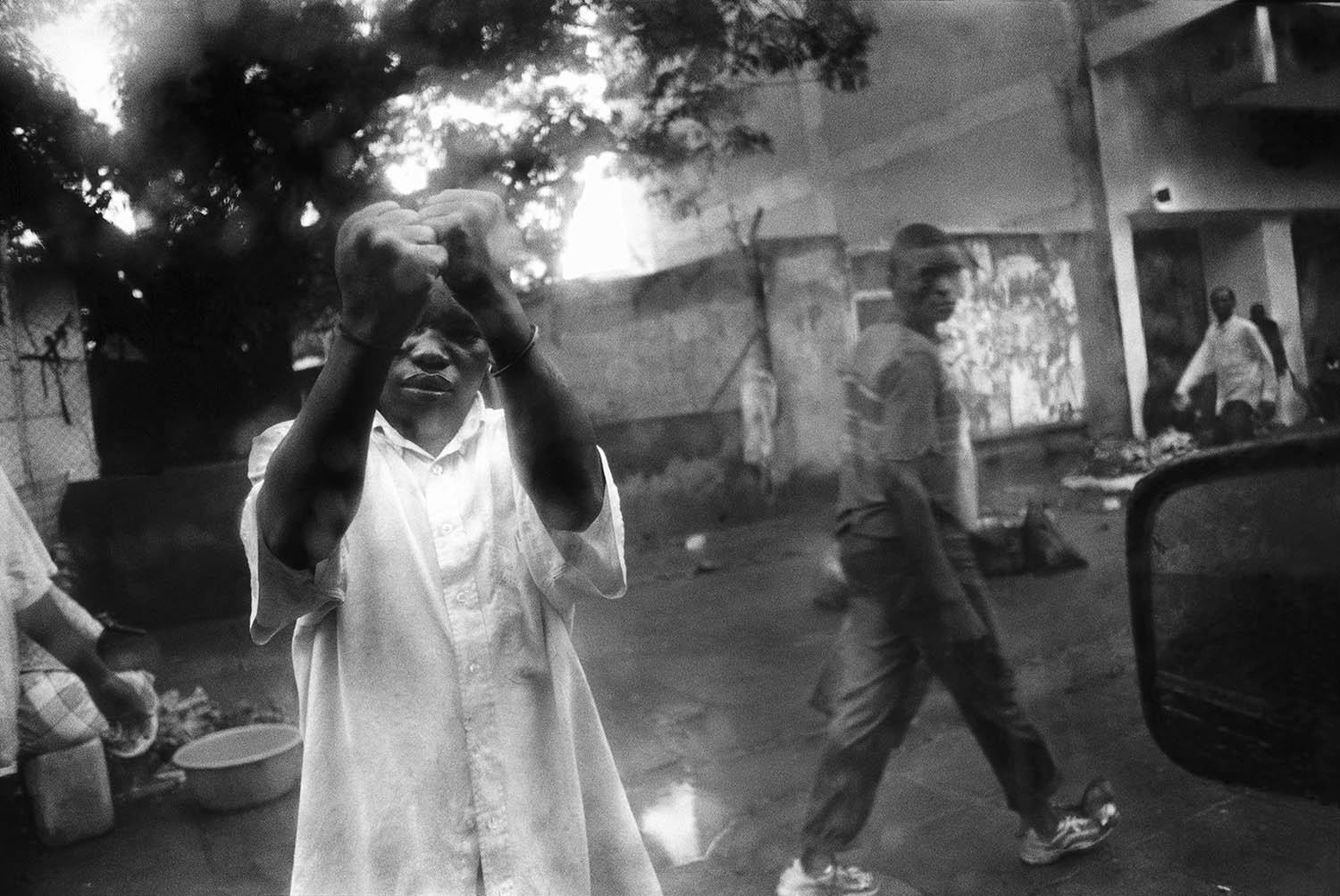

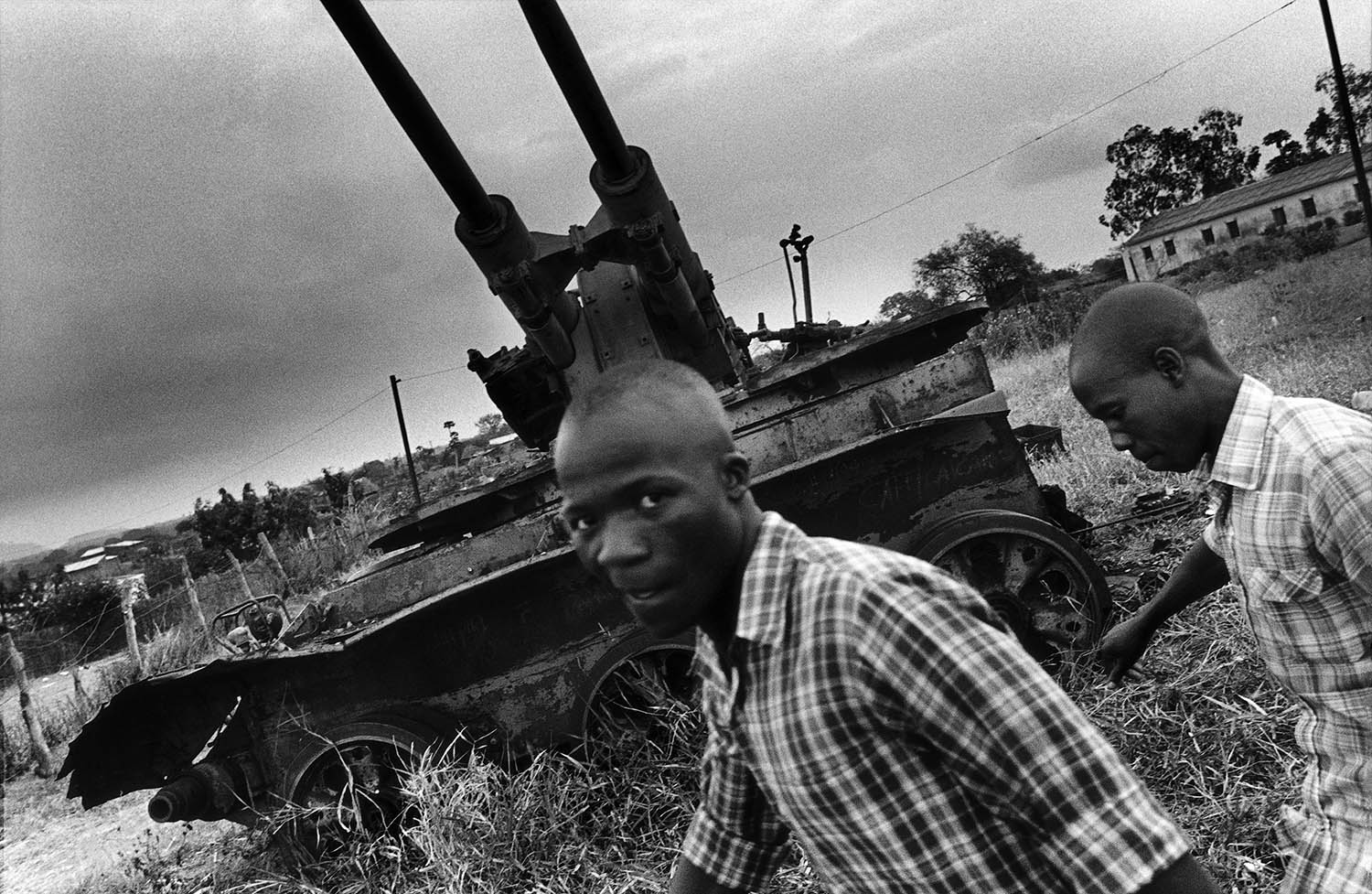

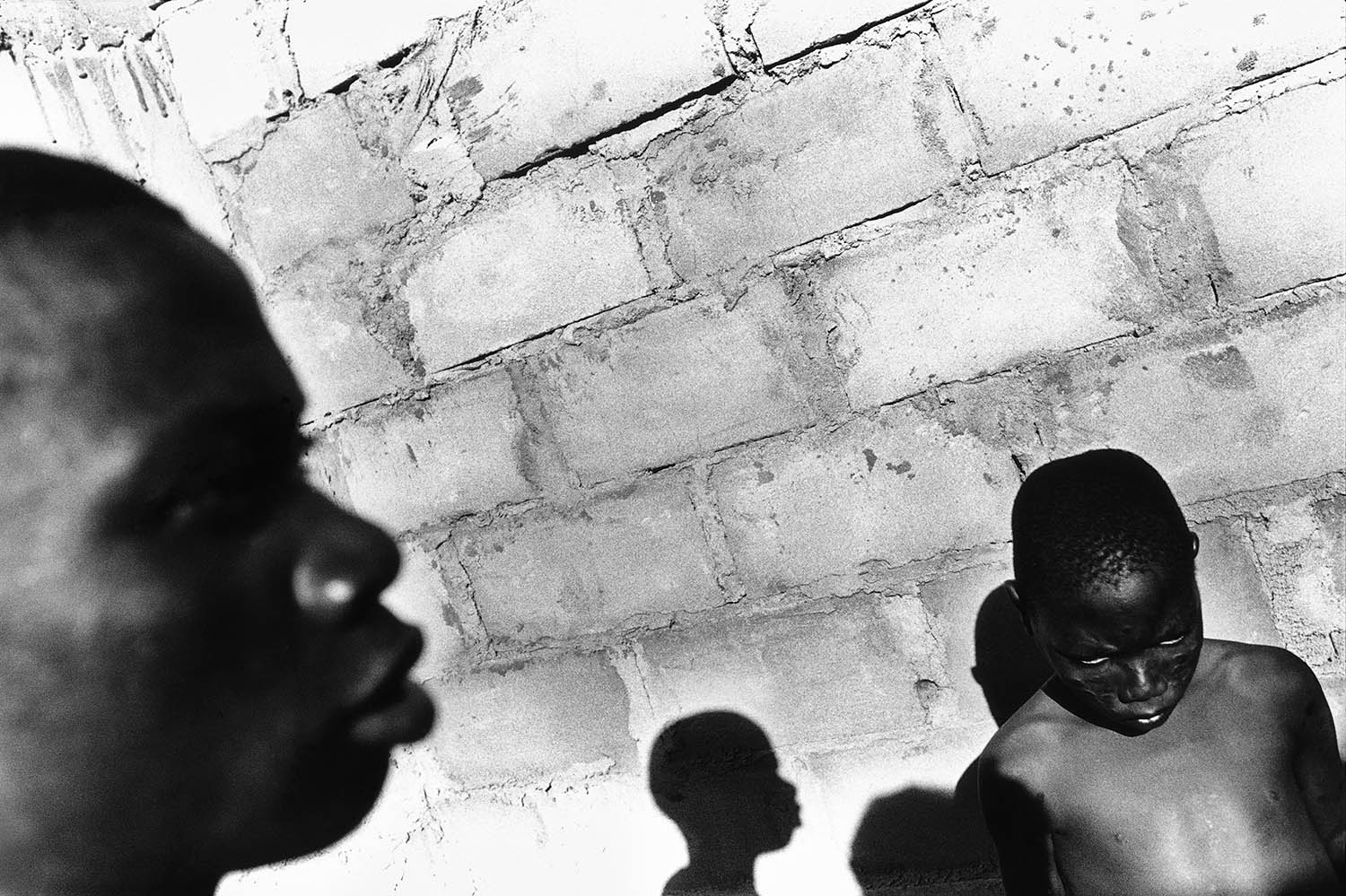

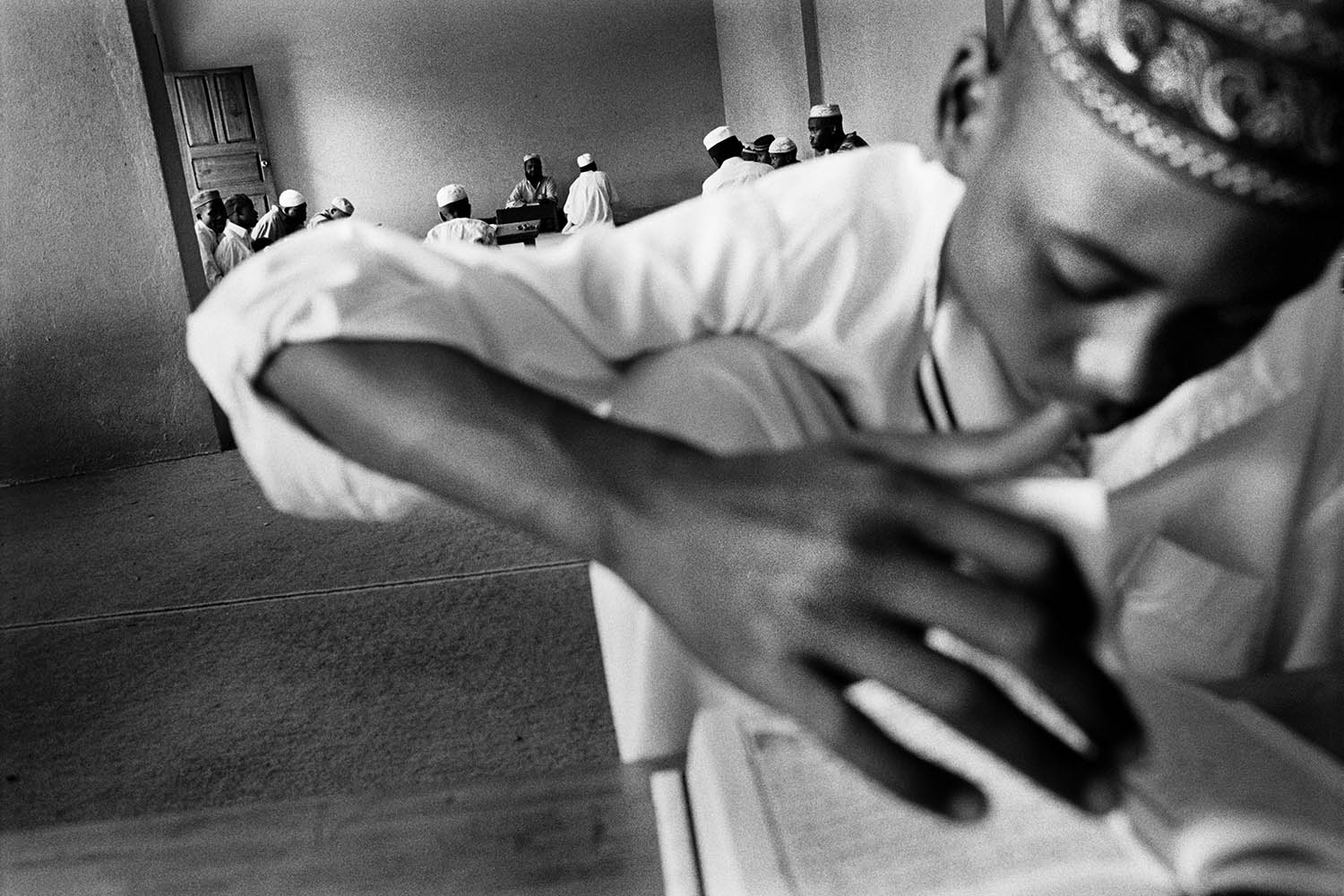

Massimo Mastrorillo con queste sue foto del Mozambico, ci fa una domanda inquietante: perché questa miseria umana che la macchina fotografica non riesce ad evitare? Trascorsi trentuno anni dalla tanto desiderata e incoraggiata indipendenza dal colonialismo portoghese, e 16 anni dall’Accordo di Pace tra il partito Frelimo e il movimento di guerrilla della Renamo, la maggior parte dei mozambicani vive nella povertà più desolante. Ma vediamo di nuovo queste immagini e osserviamo il legame di affetto e comprensione che si stabilisce tra lo sguardo del fotografo e lo sguardo del soggetto. E dobbiamo riconoscere che il messaggio di Massimo è che anche se queste persone stanno con le mani vuote, hanno fame, sono malate, o non hanno una casa decente, non hanno rinunciato. Queste immagini del paese dove viviamo ci danno fastidio? Senza dubbio. Ma sono necessarie e dobbiamo avere il coraggio e l’onestà di affrontarle. Perché ci obbligano a riflettere, a cercare le ragioni dietro la miseria, l’impotenza e la solitudine umana che qui sono genialmente ritratte. E ancora più importante: ci obbligano a stendere una mano solidale e a pensare come è cruciale non abbandonare queste persone che vogliono realizzare quel che desiderano, avere ciò che hanno sognato. Durante molto tempo si è detto che la responsabilità della stagnazione e del retrocesso del Mozambico in termini economici e sociali erano il risultato delle politiche sbagliate della Frelimo dopo l’indipendenza, il 25 di giugno del 1975. Oggi si osserva con più chiarezza. L’indipendenza aveva risvegliato le menti e i cuori dei mozambicani che, per la prima volta nella storia, sembravano sentire e agire come un unico popolo, dal fiume Rovuma al nord fino al fiume Maputo al sud. È stata una data vissuta nell’euforia e nella promessa di un futuro senza oppressione straniera, a partire dalla quale i mozambicani si sentivano determinati e fiduciosi nella loro capacità di ricostruire e sviluppare il Mozambico. Questa euforia ha fatto loro sottostimare che la minoranza colonialista che aveva perso la battaglia per un’ indipendenza d’accordo con le sue regole, era convinta che poteva raggruppare forze e, con il sostegno della vicina Sudafrica dell’ “apartheid”, sviluppare una strategia che gli permettesse di ribaltare la vittoria della Frente de Libertação de Moçambique. La tattica fu di riunire queste forze in un movimento di contro-informazione e propaganda ostile alla Frelimo e formare un movimento di guerrilla che prenderà il nome di Renamo, con la Rodesia del Sud e più tardi con il Sudafrica (quando la Rodesia divenne indipendente nel 1980 prendendo il nome di Zimbabwe).La penosa marcia verso l’utopia socialista che aveva mobilizzato la gioventù mozambicana, passò, soprattutto negli anni 80, ad essere brutalmente interrotta dall’azione della Renamo. La guerrilla attuava quasi da nord a sud, limitava l’amministrazione del governo centrale, distruggeva infrastrutture sociali ed economiche e impediva la circolazione di persone e merci. E come se non bastasse, arrivarono le croniche calamità come la siccità e i cicloni. Gli stessi aiuti umanitari arrivavano difficilmente all’interno e abbiamo assistito all’esodo e al trasferimento di centinaia di migliaia di famiglie contadine verso i paesi vicini e verso le maggiori città del Mozambico. L’impoverimento dei mozambicani e la retrocessione dell’economia erano inevitabili.

Con la morte di Samora Machel il 19 di Ottobre del 1986 in un sospettoso disastro aereo, la fine che già si annunciava precipitò. Il successore ovvio dentro l’apparato della Frelimo, Joaquim Chissano, ex-ministro degli Affari Esteri, era una personalità naturalmente diplomatica e conciliatrice. Dall’ 86 al 92 ha condotto il progressivo accomodamento ai dettami dell’Occidente, moltiplicando i contatti con le autorità del Sudafrica, mentre il campo socialista si trasformava dal di dentro e cadevano i “muri di Berlino”. Il processo culminava con l’Accordo di Pace firmato a Roma con il patrocinio di varie entità, Comunità di Sant’ Egidio in primis. La nuova Costituzione prevedeva elezioni multipartitiche, e le prime furono indette nel 1994. La Frelimo vinse le elezioni e Joaquim Chissano venne eletto Presidente della Repubblica. Il paese stava in pace, e con le strade più sicure e la circolazione ristabilita, l’economia migliorò significativamente. Dopo che la smobilitazione e la riconciliazione dei mozambicani, sotto l’egida delle Nazioni Unite, erano andate bene, arrivò la liberalizzazione dell’economia sotto l’egida delle istituzioni di Bretton Woods. Il Mozambico diventò il “caso esemplare” per la comunità internazionale. A metà degli anni 90 gli investitori stranieri cominciavano a portare progetti, alcuni dei quali di grande portata come la fabbrica di alluminio Mozal nella provincia di Maputo. Le statistiche parlavano di crescita economica spettacolare e i donatori volevano a tutti i costi che il Mozambico continuasse ad essere “l’esempio di successo”. Ma il popolo dell’interno, quel popolo la cui storia di sofferenza e resistenza sovrumana commoveva l’opinione pubblica nei paesi ricchi e mobilitava solidarietà e gli aiuti, quel popolo continuava e continua ancora ad aver bisogno dell’aiuto perché non beneficia di tanti e importanti cambiamenti. Oggi, la maggior calamità che si abbatte sul paese intero è l’HIV/AIDS. L’obbiettivo di Massimo ha incontrato con frequenza le vittime, in questi 4 anni che ha percorso il Mozambico raccogliendo immagini. Anche loro ci affrontano con una scintilla di speranza negli occhi mortificati. In Mozambico si sono indette altre due elezioni generali. Le ultime, nel 2004, hanno eletto un nuovo Presidente, Armando Guebuza, anch’egli delle fila del partito Frelimo. Ma il popolo difficilmente si mobilita ora per le elezioni perché la loro vita non è cambiata con i miracoli promessi della democrazia. La cosiddetta “fatica dei donatori” da un lato, e le loro imposizioni irrealistiche dall’altro, in un contesto internazionale complesso dove la sovranità, la stabilità e la sicurezza delle nazioni povere è sotto costante minaccia, obbliga questa gente anonima che Massimo ha fotografato a fare appello alla forza che gli resta per sopravvivere. Questa lotta per la sopravvivenza è una frase logora ma non ce n’è un’altra che possa descrivere meglio il Mozambico di oggi. Maria de Lourdes Torcato